Quick Win For Better Bus Service

For enhanced mobility service, access to stronger economic opportunity, and to improve air quality, Nashville should embrace principles of Bus Rapid Transit on high-volume corridors. BRT improvements would be a quick win for better bus service.

Since the 1970s, Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) systems have proliferated in cities around the world because they provide a more affordable option than light rail while providing efficient transportation to passengers and reduced interference with traffic. The principle is simple: separate bulky and frequently stopping buses from unpredictable car traffic, and streamline boarding and alighting to reduce dwell time at stations. BRT corridors can also be built more than twice as fast as light rail, at a fraction of the cost (1). Light rail can take 10 to 15 years to build. Key features of BRT, such as painting asphalt red for a dedicated bus lane, could be completed as fast as it takes paint to dry. More substantial features, such as upgraded transit stations and traffic light prioritization, would take longer to complete. The benefits of improving transit service along a pilot corridor would be immense. Access to efficient, affordable and sustainable transportation options would provide our communities with economic resilience, a healthier environment, and increased connectivity to opportunities in the city at large (2). With enough public support and political will, we could be looking at a significantly improved transit corridor in as few as one to two years.

WeGo, formerly the MTA, implemented improvements along four routes in the system under the moniker of “BRT Lite” in 2016. WeGo is aware that some of the benefits inherent to BRT are not reached with the current configuration, which lacks crucial features such as off-vehicle payments and separation from mixed traffic. Without robust BRT corridors, Nashville’s rapid growth will result in crippling gridlock, countless hours wasted in traffic, and deteriorating quality of life. Accordingly, the new dedicated Metro Department of Transportation should strongly consider the planning and construction of true BRT corridors as a top priority to address the emerging transportation challenges.

“The original 56 line is one of the reasons I moved to Madison. I wanted to live somewhere affordable but still keep relatively fast and reliable transportation to my job downtown. When they had to reduce service due to budget cuts, my satisfaction with my bus service went down. Improving the BRT on Gallatin Road would improve my commute (and my life) as well as countless others on this very busy route.”

Vision For “Quick Win” BRT Project

Move the slider to see before and after images.

To spur this process, Transit Now Nashville (TNN) examined the 56 corridor between Rivergate and Nashville National Cemetery in Madison according to the BRT evaluation framework developed by the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP). TNN also looked at ways to improve our evaluation score that could be achieved with minimal infrastructure investment. The result: the route currently scores only 23 out of 94 possible points, and small improvements to station and street design as well as the overall bus system could more than double this score to 47. This would put the 56 close to the “Bronze” standard for a BRT system.

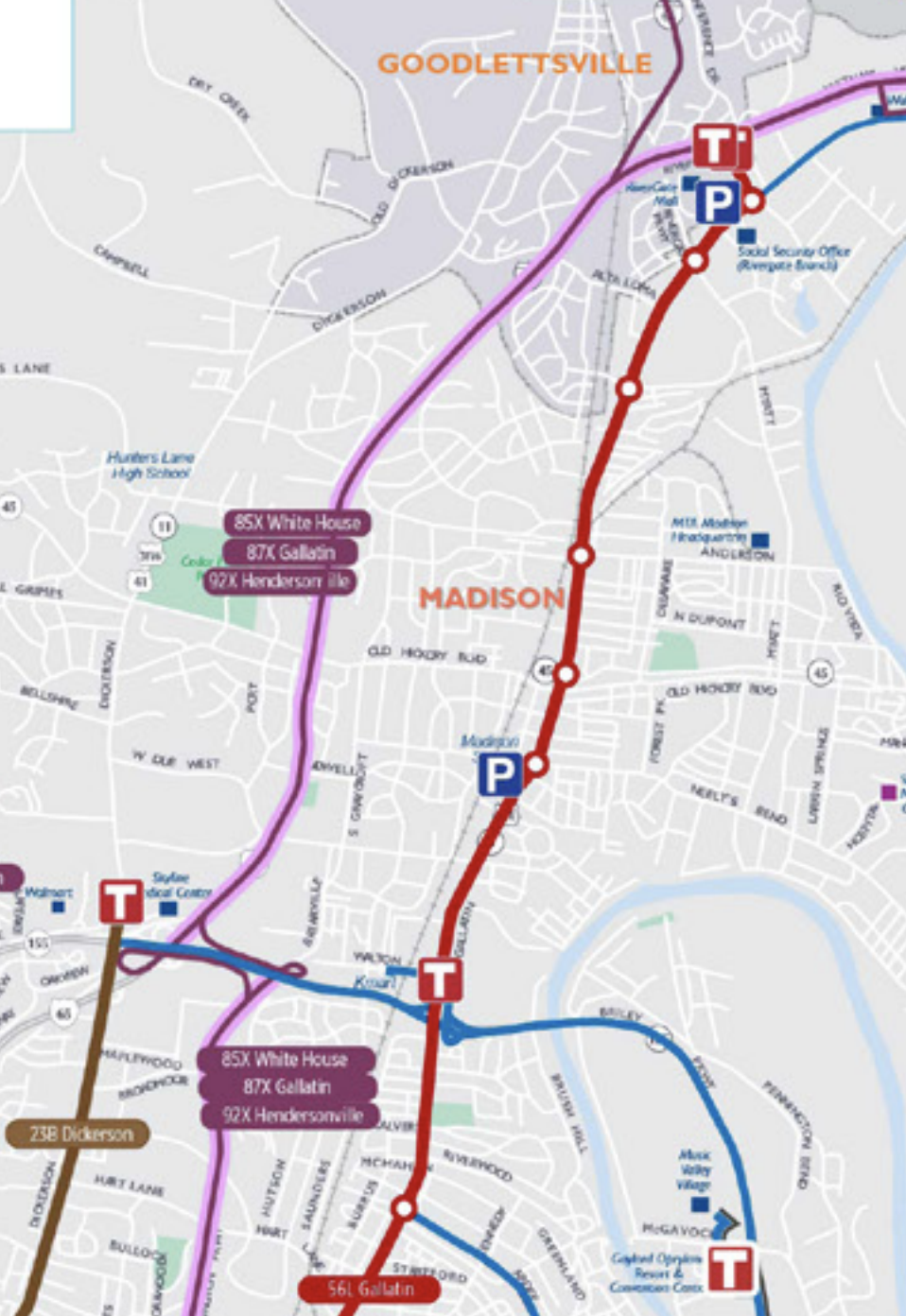

Map of TNN recommendations

Red line suggests a “quick win project” for BRT in Nashville

What needs to happen to get the Route #56 near Bronze-BRT standard? The changes needed to more than double the Gallatin corridor’s BRT level are, for the most part, low in cost and effort required, but would yield a significant contribution to an improved passenger experience. Many of these modifications can be accomplished with minor infrastructure, such as painted lines for the bus’s right-of-way, shelter at stations, bicycle parking, and improved pedestrian crossings. Some changes include improvements to operations long called for by the ridership, such as expanded hours of service and connecting corridors. WeGo already has some of these important features in the works, such as onboard validation and electric buses, which promise savings to operating costs.

See TNN’s full evaluation and scorecard results.

View of Gallatin Pike Madison Branch Library Bus Stop in “Downtown Madison” where Route 56 currently exists

Why did we pick this section? TNN chose this section of Gallatin based on it having the highest ridership city-wide (3), the width of the street, existing developments and attractions. With bus ridership on Route 56 being the highest in the city, the greatest number of existing riders would benefit. The additional service efficiency and capacity would then incentivize even greater use. Increasing service hours later into the night, beyond peak commute times, can make it possible to use transit for non-work trips, school, care-giving, and shift work trips. The segment already aligns with the Madison Circulator (Route 76), which is one of the few routes that covers a service area beyond the spokes-of-a-wheel network. The corridor also serves surrounding businesses, the TriStar healthcare facility (Madison Campus), and many affordable housing properties such as Madison Towers and Gibson Creek Apartments. In addition to the current amenities and ridership, the proposed development of “Downtown Madison” and the Madison Town Center will create a type of transit oriented development at the southwest corner of Neelys Bend and Gallatin. The increased density of housing and business opportunities will generate more demand for efficient public transit at this new hub.

The nMotion Plan (Nashville’s long range regional transportation plan) recommends a park and ride center on a light rail line at this location. BRT could be one step towards high capacity transit with a much more affordable price (BRT can be up to 60% less to construct than light rail and can take less than half as long to construct).

Madison Section of nMotion Plan

nMotion Plan Madison Section

nMotion Key

What is the reward? As an example of the benefits to be reaped, consider the time spent traveling the corridor we studied. Currently, it takes a bus rider around 30 to 40 min to get from the Rivergate Walmart to Briley Parkway (locations of proposed nMotion Transit Centers along the Gallatin corridor). With the implementation of BRT infrastructure such as dedicated bus lanes and signalized lights, prioritizing buses throughout this section of Rivergate and Madison, we estimate this travel time could be reduced to about 15 minutes. The one-hour (or longer!) bus commute from Rivergate to downtown Nashville would come down to about 35 min.

Other bus routes that use the proposed Gallatin BRT Corridor, such as the Madison Circulator, would benefit from the improved infrastructure as well. For a comparison, Richmond, Virginia’s Pulse BRT reduced travel times on the corridor 33% (4). Cleveland’s Healthline BRT along the Euclid Avenue corridor reduced travel times 26% (5).

Building higher capacity transit corridors can also be great for incentivizing new development. To ensure that existing residents benefit from increased economic opportunity, and to minimize gentrification and displacement, it is imperative to have zoning and planning strategies in place. A primary anti-displacement strategy is the protection of existing affordable housing, while making it easier, and less expensive, to build new affordable housing along the BRT corridor. Zoning for affordable housing in Nashville has become especially difficult due to the actions of the state legislature (6), which has made it even more important to consider every creative option.

Transit Oriented Development (TOD) can be built along the corridor as well. TOD with the inclusion of affordable housing would directly address the impact of transportation on overall higher living expenses (7). Changes to zoning near proposed BRT stations can set the table for denser, transit supportive, walkable mixed-use developments, with a reduction or elimination of parking requirements. Near the BRT stations, separate parcels of land owned by public municipalities could be combined to form larger development sites, with the condition that a high percentage of affordable housing is built.

There are great health benefits from the combined positive impact of BRT with electric buses, TOD, and improvements to sidewalks and bikeways. Electric BRT vehicles are not only cleaner in their own right, but they’re also a compelling alternative to private automobile use, which can take cars off the road. TODs with improved infrastructure for pedestrians and cyclists can reduce reliance on motorized traffic for everyday trips. The cumulative effect would not only help people meet a minimum healthy amount of physical activity (8), but it would reduce air pollution too. For this stretch of Gallatin Pike, air quality improvements are a matter of environmental justice. Hadley Bend on the Cumberland River is only a mile away and is reported to have some of the worst industrial air pollution in the state (9). This combined with particulate air pollution, largely caused by vehicles, has unfortunately been shown to have a negative impact on recovery from Covid-19 (10).

With a million more people on track to move into the Nashville area by 2045 (11), and traffic congestion already among the worst in the nation (12), our transit circumstances can and should be made better, sooner than later. To meet the challenges we’re facing, a healthy sense of urgency doesn’t hurt, and BRT is a great place to start. Upgrading a bus line in this concerted way makes the service more visible, usable, and reliable. Such improvements to the efficiency of our existing infrastructure would be a quick win with a powerful triple bottom line:

People who already use the bus system, many of whom are essential workers, will benefit from shorter, easier, and more predictable commutes. The extent to which everyone relies on essential workers has come into sharper focus bringing home the fact that transit itself is essential.

Increased awareness and better service quality will lead more Nashvillians to consider the bus as an attractive option to reduce their time spent behind the wheel.

A more efficient and better utilized bus system will help us alleviate the growing pains of higher living expenses, traffic congestion and poor air quality, while improving access to economic opportunities and contributing to sustainable growth.